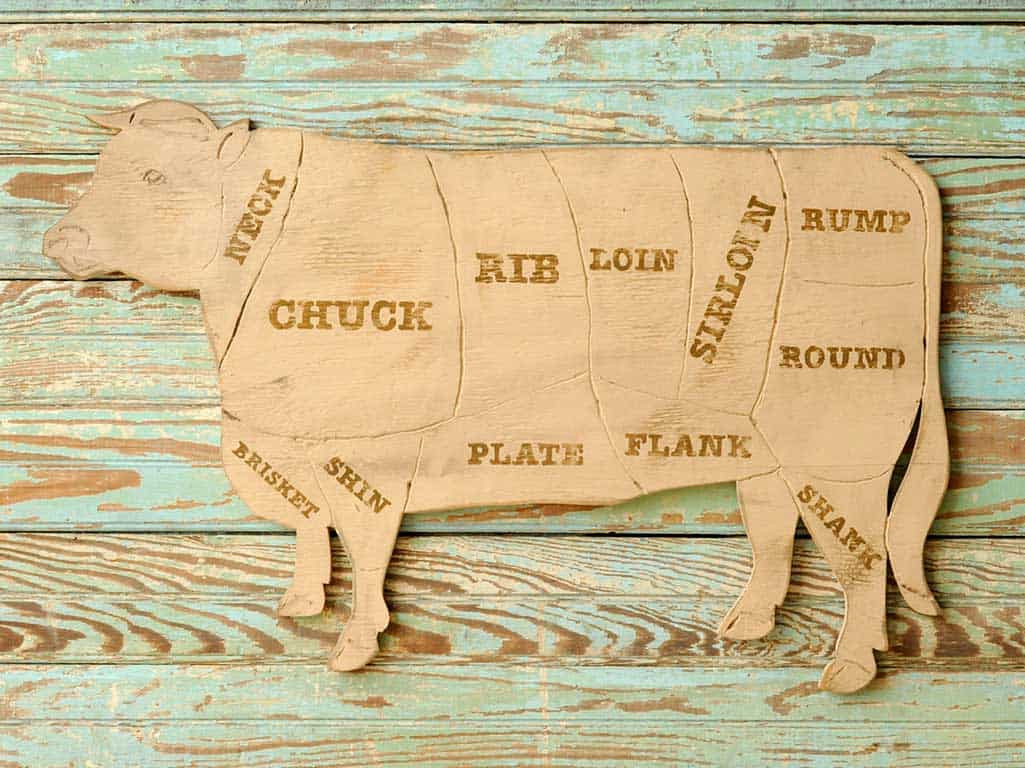

It’s unfortunate that the names used for cuts of beef can be confusing for customers. The terminology can differ from county to county, from store to store, from butcher to butcher. And that’s without looking at the terms they use in North America. This is a butcher’s guide to help everyone understand the terminology used to name cuts of beef.

Terminology

While it’s natural that people in different places develop their own preferred words for things, the terminology for cuts of beef has become nigh-on meaningless. Butchers have had a marked tendency over the years to rename cuts in an attempt to rekindle consumers’ interest. That tendency became very pronounced in the 1970s in the UK, and the USA when Price Control policies came in, in all three countries butchers simply renamed cuts to escape the price controls attached to the more well-known names. And then the marketing people lost the run of themselves trying to turn every cut into a premium item.

Unfortunately, all this jargon was only understood by people in the trade. A lot of customers were embarrassed that they didn’t understand something like the names of beef cuts. But those were the good times when beef farmers and retailers had so many buyers they didn’t really notice the ones who were intimidated by their lack of knowledge. Sales were still OK, with people who did buy sticking to the cuts they knew and understood.

The good times went wrong in the last decade of the 20th century. The word that beef was not good for you was all over the health news. People got sick from minced beef and died. The chicken farmers promoted white meat at a time when white wine was all the rage. The beef market tried to fight back and gained a little ground, but they still didn’t understand that when potential buyers came to the meat counter, they were confused by the range of cuts. Then we had foot and mouth disease, and then the biggest demon of all, BSE. Customers deserted the meat counter in droves, sales dropped, and with all else going wrong, taxpayers started grumbling about grants and payments to any businesses, including agricultural ones.

Beef farmers and retailers needed to get customers back to the meat counter, but in the meantime, the consumer had been buying chicken and fish and the clear, standard terminology they used made it easier to know how to cook and serve them. Chicken and fish were much more convenient for everyday meals. And they were being touted as healthy alternatives.

Something had to be done about the confusion at the meat counters and butcher shops. Canada was first with the renaming. The point of the renaming is to describe where on the animal the cut comes from and to let consumers know how to cook their purchase. The packaging also carries suggested cooking directions. Beef purchases have gone up by 15% in stores that have switched to the new names over stores that haven’t. Consumers have even started buying cheaper in price but quality cuts of beef that they had never used before. Sales of pot roasts went up by 150% once people knew how to cook them.

Grass-fed versus corn-fed Beef

There’s no doubt that given a choice, cows would eat grass. For millennia, cows were let graze for grass and other green leaves. In Britain and Ireland, grass-fed cattle are still the norm. American farmers discovered that feeding grain to cattle allowed them to be ready for slaughter earlier, and so corn fed beef became the preferred method of raising beef. Corn-fed cattle required antibiotics to counteract the problems in their digestive tracts caused by having a diet of corn. And growing corn to feed to cattle causes its own environmental problems, with the pesticides and fertilisers required adding to the mix.

Ageing Beef

Ageing is the controlled natural decomposition process of beef. Beef is aged to tenderise it, allowing enzymes that are naturally present in the meat break down muscle fibres. Many experts say that most of the benefits of ageing happen in the first week or two and that after that, the increase in benefit tapers off. The real Beef aficionados and really premium butchers age beef for up to 5 weeks, and swear by the flavour of the beef after the prolonged ageing.

Dry ageing

Meat (usually beef) is hung uncovered in a cold room with controlled temperature and humidity. Temperature is kept at about 1 degree C (33 F) and relative humidity at 84. If the air is too moist this will cause the meat to spoil quickly. If it is too dry the moisture loss will be too great. The meat loses moisture as it ages and as the moisture evaporates, it concentrates the flavour of the beef. When a beef cut, say prime rib, is dry-aged, as well as the evaporation loss, there is the weight loss from trimming heavily discoloured meat off the outside surfaces. This is why dry-aged beef is more expensive – the weight loss can range from 15% to 40%.

You will notice that dry-aged beef has a deeper colour and doesn’t drip like wet-aged meat.

Dry ageing is done with the premium cuts – the sirloin, ribs, fillet – dry ageing shins and necks will not make them noticeably more tender, and the premium price would put customers off. To understand the economics of this you have to take into account the weight loss, storage time, refrigeration costs and the trim loss. Trim loss is when the outer cut surfaces dry out to a very dark skin, which has to be removed and discarded

Dry ageing has been practised by traditional butchers for years and now the supermarkets are getting in on the act, and of course, promoting it as a premium product.

Wet Ageing

Wet Aged Beef is vacuum-sealed and that means humidity control is not required, which means not much evaporation takes place, so very little shrinkage. The shrink loss is kept down to about 2% but this also means that the concentration of flavour doesn’t happen as with dry aged.

beef with a covering of fat and you can be sure it will taste better than the “lean” version

Meat that has been wet-aged will have a brighter colour than dry-aged meat. It will be a lot wetter than the dry-aged equivalent cut and fans say that it doesn’t grill or barbecue properly. They say that it steams in its own juice and is missing that charred, BBQ beef flavour. Most of the beef on supermarket shelves has been wet-aged because it is cheaper and more convenient to store that way.

Lean v Fat

Low fat has become a mantra, and farmers try to have their cattle with little fat for presentation at meat factories. The factories penalise farmers for high fat scores because they say, the consumer wants lean meat. This meat will dry out more easily during cooking. This also has an impact on the flavour of beef – lean means less flavour.

Look for beef with a covering of fat and you can be sure it will taste better than the “lean” version. You don’t have to eat the fat, but you should cook with it on the meat.

Fat through the muscle is called “marbling” and is much prized among aficionados. This fat marbling melts during cooking and gives a much juicier beefy flavour to the meat.

On a whole carcase, fatter beef will keep longer than very lean beef because the fat is a protective covering.

The meat cuts you see in packs in the supermarket are wrapped in a permeable film that lets air through to keep the meat a bright red colour.

Beef normally has a more purple colour. It only turns red when it comes into contact with oxygen. That rosy red colour is the colour that customers associate with “safe to eat.”

Supermarkets attract us by packing fresh Beef in a film which is actually specially selected to let air through, to ensure the surface of the meat is that bright red colour.

Another message here : Don’t freeze meat in the pack you got in the supermarket. It needs proper freezer wrap or you will have meat with freezer burn.

What’s at “steak”?

Steak is a term for slices of beef from about 100 gm to anything up to 1000gm and refers to many different cuts of beef. The steaks you will get in a restaurant are generally Fillet, T-Bone, Ribeye Steak and Striploin.

Where do the steaks come from?

All of these steaks come from the same general area toward hindquarter of the animal: the loin, and the ribs. These are muscles that don’t do any heavy work and don’t have the connective tissues that need long cooking times to break down.

The result is, these steaks are so much more tender than the other cuts of beef, and grilling, frying or BBQ with intense heat are all you need to char the outside of these meats while the inside can be as rare as you like

Do you like tenderness, or flavour? Or a combination of both?

Why are these steaks so expensive?

As a percentage of the whole animal these cuts are only a small fraction, so their rarity, combined with the cost factors from ageing etc., make them premium cuts.

For example, the full fillet is only 1.8% of a side of beef and the striploin comes to 4.7% while the round and the chuck account for 52% of the total.

That means there is an awful lot of beef on a side that is not steak quality.

As this meat is expensive, it’s worth finding out how each one is different so you buy the one that suits you best! Do you like tenderness, or flavour? Or a combination of both?

Types of Beef Cuts

Here’s the skinny on each cut so you can make an informed choice.

- Fillet

- Striploin

- T-bone

- Rib-Eye

Fillet

Other names: Filet mignon, tenderloin, Chateaubriand, fillet.

How it’s sold: In thick slices boneless; it is the most expensive steak. The smaller end is called Filet Mignon. Also called Eye Fillet. Fillet is one of the very lean cuts.

Where it’s from: Under the short loin. A whole tenderloin tapers at one end (the “tail”) and the Chateaubriand is from where it thickens out.

What it looks like: Small and compact. The meat is fine-grained in texture and lean. Because it is smaller, fillet steaks are usually cut thicker than other steaks.

What it tastes like: The most tender of all the steaks and very lean, fillet is buttery and mild in flavour.

How to cook it: Cooking methods can vary. Sear the outside until browned, finish in the oven. Or the reverse sear, place in the oven then sear afterwards.

Striploin

Other names: New York Strip, Manhattan, Kansas strip, top sirloin, top loin, contre-filet

How it’s sold: Boneless

Where it’s from: Short loin above the Fillet

What it looks like: There is some fat on one edge of the steak but with no large pockets of fat. The texture of the meat is fine-grained.

What it tastes like: With medium fat content, Striploins are tender, but not as tender as Fillets or Rib Eyes, and have good, beefy flavour.

How to cook it: Cook over high heat — pan sear or grill.

T-Bone

Other names: Porterhouse

How it’s sold: Bone in.

Where it’s from: A cross-section of the short loin

What it looks like: A T-shaped bone with meat on both sides of the long bone. On one side is a piece of the Fillet, and the other side is Striploin.

What it tastes like: You will get the best of both worlds with this cut: tender Fillet, and juicy striploin steak

How to cook it: There are two different kinds of steak in one cut, so you have to be careful when cooking since the Fillet will cook more quickly than the Striploin. BBQ, fry or grill, keeping the Fillet portion out of the direct heat.

Rib Eye

Other names: Scotch Fillet, Delmonico, Entrecote

How it’s sold: Bone in (Tomahawk or Cowboy steak) or boneless

Where it’s from: Between the 6th and 12th ribs. Rib Eyes are steaks cut from a prime rib or standing rib roast.

What it looks like: Lots of marbling through the meat and large pockets of fat throughout. The central eye has a fine grain while the outer section has a looser muscle structure.

What it tastes like: Great beef taste, juicy, and full of flavour.

How to cook it: Cook over high heat — pan fry, BBQ or grill.

Less well-known beef cuts

Flank Steak. Sometimes called Skirt Steak This is a really good cut of beef. Used for Fajitas and can be rolled, stuffed and roasted.

Picanha. Also called Rump Cap or Coulotte, this is one of the secret cuts of beef you need to know about.

Leave a Reply